21 . 11 . 2019

Calcium - How to Ensure an Adequate Intake

Calcium is an essential mineral for the functioning of the human body. About 99% of calcium is deposited in bones and teeth, and the remaining 1% in blood and soft tissue. In this article, we explore its importance in physiology and the primary sources in the diet.

What is calcium’s function in the body?

In addition to bone and teeth mineralization, calcium participates in other fundamental biological processes, such as the following:

- muscular contraction

- regulation of vasoconstriction and vasodilation

- blood pressure control

- nerve signal transmission

- heart rhythm regulation

- secretion of insulin and other hormones

- coagulation system

How do we absorb calcium?

Ingested calcium is not isolated, but rather in the form of salts such as calcium citrate, calcium carbonate, and others. For absorption to occur, calcium salts must be solubilized, which requires an adequate gastric pH. If the gastric pH is too high (as in people who have problems with the cells secreting hydrochloric acid, or during prolonged use of proton pump inhibitors), calcium absorption will be compromised.

Calcium is mostly absorbed in the small intestine and only a tiny fraction in the colon (4-10%). As such, we should be mindful of the health of our intestines, as anything that affects the function of the enterocyte may also affect calcium absorption.

What percentage of calcium is absorbed?

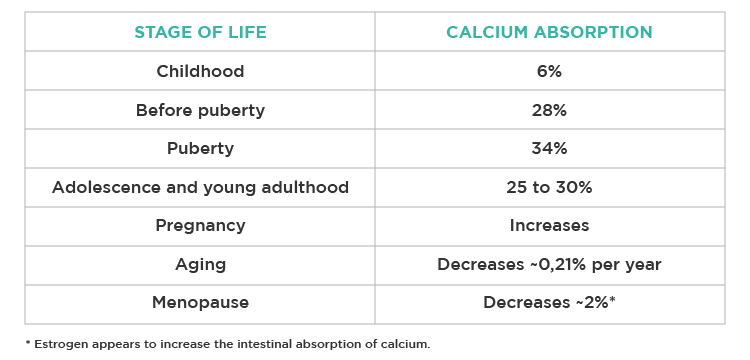

Until adulthood, the absorption capacity of calcium increases, reaching a maximum absorption rate of 30%. As one gets older, the calcium absorption capacity decreases, as shown in the following table:

Fig. 1 – Calcium absorption capacity at different stages of life.

Evidently, other hormonal factors influence calcium absorption, namely PTH (parathyroid hormone), calcitriol (activated vitamin D), thyroid hormones, estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone.

How is calcium concentration regulated in the blood?

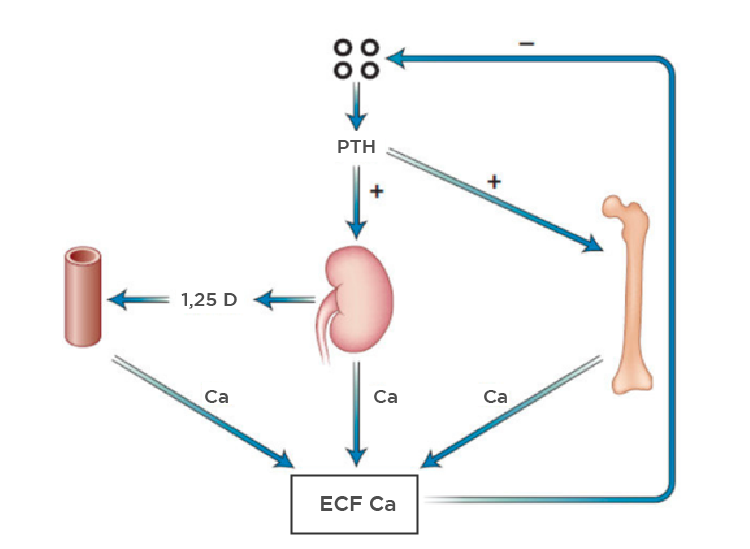

Although only 1% of total calcium is in the blood, this concentration is strictly controlled by the body, because small deviations can have significant repercussions. The main players involved in calcium regulation are PTH and calcitriol.

When calcium concentration lowers, specific sensors are activated in the parathyroid glands, which promote PTH secretion. This process will result in an increase in serum calcium through 3 mechanisms:

- Increased bone reabsorption: assuming we have about 1 Kg of calcium stored in the skeleton (for a 70kg individual), this is then the main reservoir used to keep the calcium concentration stable. However, this will imply demineralizing and weakening the bone.

- Increased intestinal absorption: PTH promotes the activation of vitamin D to calcitriol in the kidney, which in turn increases the absorption of calcium in the intestine.

- Increased renal calcium reabsorption and increased phosphorus excretion.

Hypercalcemia is less common, occurring only in situations of vitamin D toxicity (above 625 mcg/day), PTH-producing tumors, or high bone turnover.

Fig. 2 – PTH is the main regulator of the serum calcium concentration, exerting its effects on the bone, kidney and intestines (indirectly through calcitriol).

What are the signs and symptoms of calcium deficiency?

As hypocalcemia sets in, signs and symptoms may arise gradually. The most common symptoms are:

- lack of memory and confusion

- depression

- muscle spasms and cramps

- paresthesias (tingling sensation) in the hands, feet and face

- osteopenia and osteoporosis (bone demineralization)

- dental caries and other teeth problems

- increased blood pressure

How much calcium should we consume?

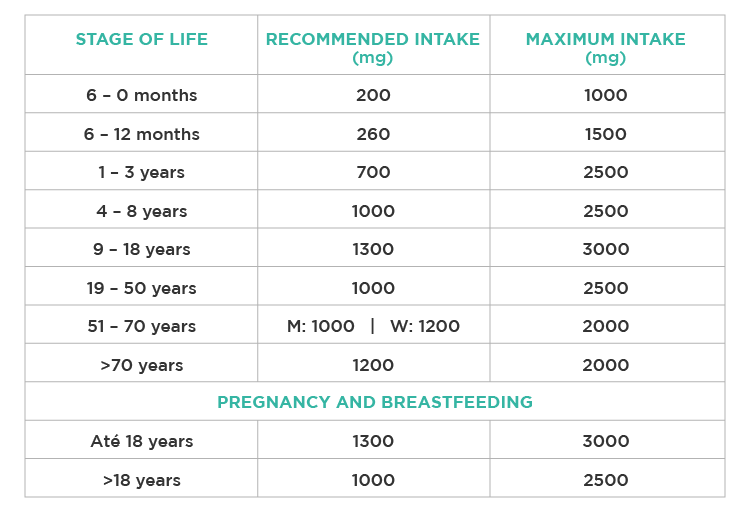

It is considered that an adult should consume about 1000 mg of calcium per day. There is evidence, however, that individuals with diets lower in sodium and protein (with a lower acid load) may need less calcium to function.

Fig. 3 – Recommended daily dose of calcium for the different stages of life.

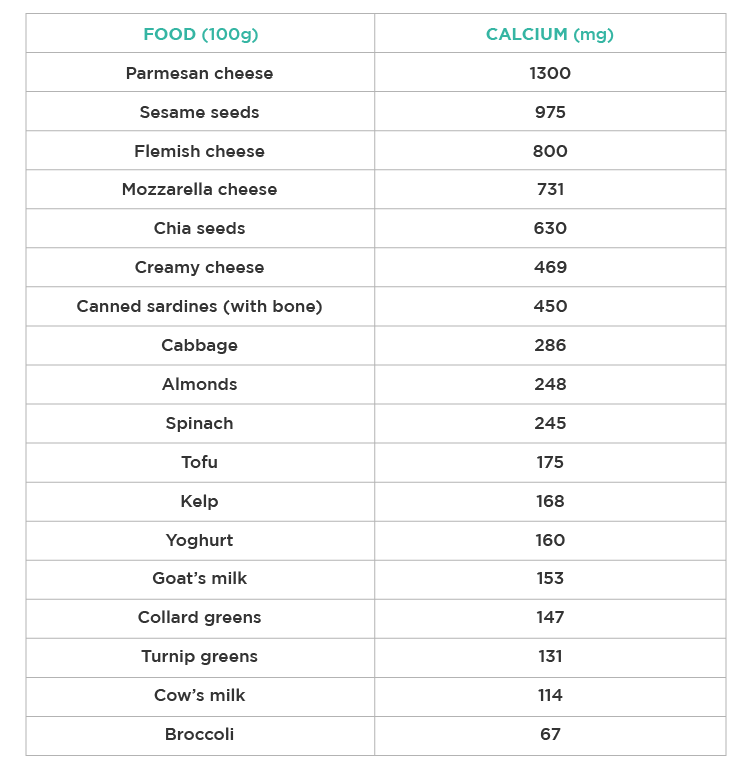

What are the primary dietary sources of calcium?

Dairy products are the main source of calcium in the diet. However, there are other ways to ensure adequate intake, namely through certain canned vegetables, seeds, and bone-in fish.

Fig. 4 – Amount of calcium present in 100 grams of different foods.

The absorption rate of different calcium sources varies depending on other substances present in the food. For example, spinach is a poor source of calcium because it has a high concentration of oxalates that interfere with calcium absorption (only 5% for spinach). In turn, we can absorb about 50% of calcium from cabbages, and 30% from dairy.

Should we resort to calcium supplementation?

There is some evidence that calcium supplementation may increase cardiovascular risk. This may be due to the sudden and transient increase in plasma calcium concentrations after supplementation.

Although this association is not consensual, we should prefer food as a source of calcium, as is the case with other nutrients.

If supplementation is required to ensure adequate intake, there are several options available, such as calcium salts (citrate, carbonate or gluconate) or calcium microcrystalline hydroxyapatite (bone lysate).

As we have seen, the effect of calcium goes far beyond the mineralization of bones and teeth and plays a key role in the muscular, hormonal, and cardiovascular systems. Perhaps this is why its concentration is so precisely regulated by the body.

By following a diverse diet containing cabbage, dairy products, and bone-in fish, we can ensure an adequate daily intake of calcium.

Article written by Susana Augusto – Clinical Nutritionist

References:

Ross AC, Caballero B, Cousins RJ, Tucker KL. Modern Nutrition in Health and Disease 11th Edition. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2012.

Mataix J. Nutrición y Alimentación Humana – Tomo I: Nutrientes y Alimentos. Ergon, 2002.

Khanal RC, Nemere I. Regulation of Intestinal Calcium Transport. Annual Review of Nutrition. 2008;28(1):179-196.

Holford’s P. New Optimum Nutrition Bible. Piatkus; 2004.

Ross AC, Manson JE, Abrams SA, et al. The 2011 Report on Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D from the Institute of Medicine: What Clinicians Need to Know. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2011;96(1):53-58.

Hunt CD, Johnson LK. Calcium requirements: new estimations for men and women by cross-sectional statistical analyses of calcium balance data from metabolic studies. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2007;86(4):1054-1063.

Protuguese Platform of Food Information (PortFIR). Retrieved from http://portfir.insa.pt/#

Titchenal CA, Dobbs J. A system to assess the quality of food sources of calcium. Journal of Food Compos Anal. 2007;20(8):717-724.

Recker RR, Bammi A., Heaney RP. Calcium absorbability from milk products, an imitation milk, and calcium carbonate. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1988 Jan;47(1):93-5.

Heaney RP, Weaver CM. Calcium absorption from kale. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1990 Apr;51(4):656-7.